We’ve gotta stop doing this. The indomitable gears of fashion are whirling overtime with last week’s news of Demna Gvasalia’s appointment, ushering in a new era of Gucci and leaving his old seat open. Everyone has opinions about what should come next. Fashion spectators may want to join hands with watchers of Severance—the way people talked about Ricardo Tisci’s recent Instagram wipe, it might as well be a Lumon theory. We are that one guy hanging news clippings in a room lit by a tiny gas lamp, tangled up in a web of strings and pushpins. I’m tired.

The newest slew of highly anticipated debuts have hit the Paris runways, and although the rumor mill is great fun, we don’t have to gossip in circles until the next headline drops. Slow down with me for a bit! Let’s take a careful look at that one name so many were dropping in reference to the Balenciaga job last week. We will examine her polysemantic design language, and then maybe I’ll let you see what I wore to Berghain…

Martine Rose

Martine Rose is a Jamaican English menswear designer. She dressed Kendrick Lamar for the Super Bowl and is responsible for the neon Nike Shox mules fashion girls have been drooling over since 2023. Rose makes cool, wearable clothes—that’s where much of the internet discourse seems to stop.

This season of designer musical chairs is reminiscent of the rumor mill right before Pharrell Williams was appointed as Creative Director at Louis Vuitton in 2023. There’s a recurring dialogue about the lack of diversity at the top of goliathan luxury fashion houses, and Rose’s identity has often been wielded as a talking point in succession chatter, without espousing substantial conversation about who she is as a designer and why she might be a good fit. Online fashion critic Rian Phin (@thatadult) speaks about this in a recent Tiktok.

Much of the virtual talk about Rose has focused on reductive comparisons and contrasts between her and a handful of modern contemporaries like Demna and Wales Bonner. It’s easy to gamify the shuffling of leadership roles in fashion, a pool of designers jockeying for a conveyor belt of newly open heritage house positions, but this plug-and-play can obscure us from taking a deeper look at what’s going on. Who knows if she even wants to go to Balenciaga!

It is well known that Rose, who started her label in 2007, was a major inspiration for Demna’s approach at Vêtements and Balenciaga, most popularly that boxy tailored silhouette. He has been a vocal admirer of her work since his Louis Vuitton days in 2013, to when he invited her to design for the Balenciaga menswear collections two years later, from 2015 to 2018. Rose has had an undeniable impact on the way people dress during her tenure in fashion, defining silhouettes that stuck, like superwide pants and big suit shoulders.

In other words, Balenciaga has an obvious connection to Rose. But upon sitting down to research, it surprises me that I heard no mentions of her name for the Margiela job before Glenn Martens was announced at the end of January.

An interesting synergy emerges when examining her work concurrently with Margiela’s. It’s true that his influence extends so powerfully that he has had an impact on most current designers, from Raf Simons to Hodakova, but I would like to review his time at Margiela as an analogy that can point us towards Rose’s unique artistic prowess. Through this parallel, we illuminate what might be trickier for some to see in the moment, particularly as social media discourse is peppered with comments like “Martine Rose would just give us the same as Demna.”

Just like Rose, self-described as an “underdog,” Margiela hasn’t always been understood, confronting skepticism about his approach to the runway, ragpicker-esque tendencies, and unconventional processes. But all of this has been distilled through the amber of time—now, few in fashion can deny his impact on the way we dress.

I think of Walter Benjamin’s fixation on Paul Klee’s “Angelus Novus” painting, in flight towards the future with its gaze trained on the past, watching temporal rubble fold into itself. We can examine remnants of design history to understand what’s in front of us today.

Patterns emerge amongst prolific creatives, through their ethos and execution of visual and tactile concepts, shaping the evolution of the industry and what we see on the streets. This piece is absolutely not saying “Martine Rose is the new Margiela,” but that through comparison, we can dash through the labyrinth of history with an ontological key.

Humanistic Fashion

There is a levity, an unpretentious rebellion to Rose’s brand reminiscent of the Martin Margiela days. Humble confidence and humanistic zeal in an industry that can feel so rigid.

Take Margiela’s legendary SS1989 collection, held on a children’s playground in the 20th arrondissement of Paris. The fashion crowd was whisked far from typical show locations in the Carré du Louvre and sat alongside neighborhood children who granted the designer permission to use their space. At the end, the kids organically spilled onto the runway with infectious energy. It was palpably fresh and joyful. The coterie of Margiela girls—partially street casted—walked an uneven dirt ground with their regular gaits rather than the glamorous struts in vogue at the time.

Fashion for Margiela was slice-of-life. He solicited styling opinions from the models and conveyed curiosity through his craft. His shows explored the role of garments on the body, strange vestiges swept up in motion. Despite disapproval from critics who called his first shows a “Salvation Army mood,” it carried optimism, new ideas, and a sense of togetherness. People cried.

It was also executed with skill. When Margiela conceptualised a backwards dress shirt or a frankensteined pants situation, it was done with deliberate maneuvers of technique. These were earnest and conscientious commentaries on style and the process of creation.

He continued to stage shows in unconventional settings like the Paris metro, a car parking lot, and the Salvation Army—a cheeky comeback to those critics. In one show, a model walked with her spouse carrying their baby.

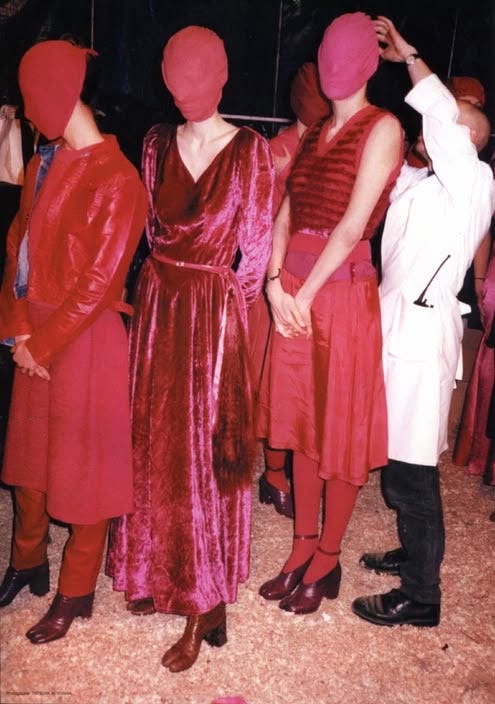

Margiela encouraged intentionally messy hair, once dredging a model’s extensions in the dirt to create a disheveled look. Even the edgy AW1995 show at a circus in the 16th arrondissement, where models wore austere face coverings, was far from solemn. With the closing walk, the spell broke. Girls sauntered out with balloons and uncovered, smiling faces, as if to say, “the work has integrity, but there’s no reason to take ourselves so seriously!”

Martine Rose uses atypical show formats in a similar fashion, to world-build and lead with sincerity. She makes carefully considered space for real people and community, showing sparingly and occasionally off-schedule in areas like Tottenham, a North London neighborhood with a rich immigration history. Rose incorporates community members in her casting and has brought the runway to her kid’s school, a climbing gym, and a covered street market. Like Margiela, she tends to show off the beaten path.

Her SS2019 collection was especially electric. Staged in a small cul-de-sac in London’s Chalk Farm, people of the neighborhood joined fashion editors outside, pulling up lawn chairs to watch from their gardens. Despite her work being intertwined with real communities, it is not extractive; different from, say, the orientalism of a Galliano show in the 90s. She pays tribute to stories underrepresented in fashion and pauses to understand them. Often, these are narratives she grew up observing.

Rose deconstructs the uniforms of everyday life and unearths a rainbow of subcultures. The styling, by Tamara Rothstein, animates character vignettes like the “bankers, office workers, and bus drivers” of AW2017. By twisting these archetypes into something new, toying with proportion and disattaching pieces from their expected context, she produces a collage of identity. Her cast of characters are a gestalt of cultural influences that one cannot flatten into a stereotype.

In her SS2017 lookbook, with its tagline “old clothes command new owners,” she recontextualizes vintage clothing, similar to Margiela’s transfiguration of old costumes for each look in his SS1993 collection. She reconfigures the football jersey by reversing badges, leaving stitching visible and obfuscating text. Things may not be semiotically legible at first glance because her work can be subtle, and yet, the mysterious feeling evoked through a combination of details is undeniable.

Through a peristalsis of references, Rose makes the familiar strange and the strange familiar—the hyperreal.

The Hyperreal

Philosopher Jean Baudrillard viewed contemporary life as a simulacrum of images and spectacle. In his view, symbolic representations have fused with reality itself, to the extent that it is almost impossible to distinguish between the two—the “hyperreal.”

Modernity is dissociative, a process compounded by the internet and social media. To what extent is the stuff we see online an accurate representation of life itself? How can we tell what’s real and what’s AI? Last week, I listened to a NYT podcast about a woman who fell in love with ChatGPT.

Martine Rose wrangles the hyperreal. Her work uses the unresolved as a means to generate radical self-acceptance, a counterpoint to algorithms that demand visual codes be neatly packaged into micro-trends.

Her surrealism is socially generative. Rian Phin does a great video on the dreamlike nature of Rose’s work (“eerie surreal design for self acceptance”)1 and her ability to make space for the “shadow parts of yourself.” The designer’s use of what Phin calls the “mystical mundane” allows her harness a cultural consciousness that moves across time.

Rose grasps at something slippery through abstraction, through sartorial strangeness. Through her perversion of silhouette, threads of the social zeitgeist are made opaque during a time when it’s difficult to put your finger on exactly how we are changing with the world around us, as impending climate disaster and political conflict hover over our heads like a noxious halo.

It’s autofiction about the luminescence of community and self-expression as resistance. How we dance, celebrate small victories, and hold hands.

The late poet Lyn Hejinian wrote “what follows a strict chronology has no memory.” There is more to life than what we can hold in the palm of our hands. There is much to be discovered by unearthing parts of ourselves that lie dormant, in the shame and fear of discomfort. There is desire, wildness, and love. Phin calls Rose’s work “seduction in the unreliable.” By bringing the “unresolved” to the light, we can accept ourselves in all of our fluctuations.

Martine Rose’s renegotiation of style codes make space for people to be themselves, particularly those at the margins. She remembers sitting on her sister’s bed as a young girl and learning how little nuances of dress “like a handkerchief or the way you tilt your hat” can alter the messages you are transmitting. Style is one of many artistic footholds into the world.

Rose’s lookbooks make a particularly potent use of the generative hyperreal. For SS2021, she researched underground queer nightlife in 70s San Francisco in collaboration with rave historian Steve Terry. It is sexy, a découpage of culture pasted to the body. There are football uniforms reimagined, miniature sports bags-turned-clutch, and a karate-style wrap jacket fluidly hugging the body. She puts men in lace lingerie and garter belts, turns football socks into delicate stockings, and perverts office wear. She’s a fairy godmother of sorts; I’m sure she could turn a pumpkin into something suave but vulnerable.

In the background, professional webcam boys pose dynamically, embodying the contortions of self experienced in lockdown. The figures standing in front of them wear an amalgam of symbols associated with non-distanced activities like going to the club and playing sports, markers of physical community.

How did we deal with a desire for normalcy during quarantine? Perhaps we burst out into the world, resplendent, in our dreams. Eyes closed, we may have taken on a form similar to Rose’s models. They are what we remember and yearn for, a manifestation of urges that cannot be fulfilled. We can see across time through this tension, our public and private selves in a state of confusion, distorted by memory.

Margiela is also no stranger to the hyperreal. He was known for a frequent usage of non-runway formats characterised by experimental, symbolically-charged spaces. His AW1998 show involved a number of artistic collaborators, including Mark Borthwick, whose short film was played at the start of the presentation. Models appeared on three screens in various states of dress against a white stage sparsely decorated with chairs and plants. Like the Martine Rose lookbook, it was a place outside of time.

At one point, three women were depicted side-by-side, talking. The placelessness allowed its subjects to roam untethered, free to inhabit their quirks and imperfections. A contrast to the chiseled, unspeaking supermodels of typical runway shows.

At the end of the film, fifteen eerie life-sized puppets styled by Jane Howe dropped from the ceiling wearing the collection, puppeteered and pacing across the stage.

Similar to the Martine Rose lookbook, this Margiela show is a portrayal of shadow selves and duality. In the first part, living people occupy a sterile film environment. Then, lifeless dolls take corporeal form in the room, right in front of the audience. In which circumstance is the clothing interacting more authentically with reality?

It’s eerie. Through tension between the body, garments, and environment of the presentation, we build upon our understanding that clothes are animated by the triumphs, joys, and sorrows experienced by the human form, all inextricably connected to the physical world.

Bodies, Bodies, Bodies

It’s “always been weirdos” says Rose. The kooky, the irreverent, the wild. The most stylish people I know treat clothing as an accompaniment to interesting lives.

Martine Rose has become known for her interpretations of football jerseys, and although she isn't a huge fan, she’s drawn to their significance in subculture. Rose remembers the club craze at the end of the 80s, when the football hooligans dropped their routine fistfights to go dancing.

“For me that demonstrates the power of culture, the power of music to change things,” she said. Her synthesis of garments associated with sports fans, club kids, and working people compose a unique semiotic soup, in which garments assume fluid meaning. Together, they forge a new story.

“She’s actually a champion of the ordinary and the bizarre–and her talent in fashion is that she doesn't make any distinctions between them, or between what's considered beautiful or ugly”

- Sarah Mower (Vogue)

Margiela also concocted new, subversive narratives by drawing from the past. In SS1991, he split 1950s gowns down the middle and paired them with jeans. Given the history of the 50s silhouette—a restrictive post-war return to body-restricting femininity—Margiela remixes the garment and flips the narrative. The refashioned dress lends the woman modern agency.

Later, in AW1997, during a decade of ultra-skinny “heroin-chic,” Margiela continued to comment on the body with the dress form itself. The stockman jacket symbolised the process of mass-producing clothes that felt designed to tame bodies rather than support them. By placing it on the runway, formed to the model’s figure like a second skin, he comments on the process of creation and societal standards. Margiela called this “semi-couture,” or half-fashion. He urged women to come as they were, confidently inhabiting their unpruned, nuanced selves. Youtuber Bliss Foster does a great video on this collection.

In a similar manner, Rose subverts the constrictions of masculinity:

“For menswear, I always like this tension between two poles. I’m using quite classic things like tailoring and sportswear, but the other pole has to be quite far apart. So I was looking at quite stately lady things, like barbour jackets cut on a 50s women’s A-line, corsetry, and pearls”

- Martine Rose

Rose likes a challenge, which is why she is intrigued by the supposed “rules” of menswear, saying “that's what I really, really enjoy: that there are still things to push against.” She obfuscates traditional gender norms in fashion as a genuine proposition, rather than a gimmick.

In the spirit of the Greek prophet Tiresias, who experienced life as both a man and a woman, Rose and Margiela grasp cross-sections of life across time to unravel threads of gender and politics. In T.S. Eliot's The Wasteland, Tiresias derives understandings about human nature by viewing the past and future superimposed onto each other. The two designers do something similar with clothes, using old nuances of style as symbols in a fresh dialogue.

Through their craft, the present and dialectical image of the past collide, creating moments of clarity, as Benjamin would say. It reminds me of Miuccia Prada’s early days, perverting military workwear associated with Italian fascism to reflect a post-war rebirth of style, marred by violence but reflecting rekindled hope.

In this way, Rose’s work is heteroglossic, a visual representation of history speaking through memory and the immortal language of fabric. She investigates social belonging through the streets of London and gives gangs of outsiders the stage, returning us to an 80s and 90s London rave scene punctuated by drum and bass and garage music. It’s not dissimilar to Margiela’s shows—where small details were sources of imagination hinting at the sartorial ingenuity of regular, creative people.

Perhaps somewhere, a young girl on the streets of Paris uses scraps of fabric to express her style, like the strips woven around fingers and thick ribbons used to make bob-like hairstyles in Margiela’s AW1989 show. Rose carries the torch of Margiela in this sense, extending this practice of narrative creation through heightened specificity, paying homage to diasporic British culture.

Both designers attempt to democratise fashion, but Rose’s work is autobiographic in a different way. Whereas Margiela frees the body and comments on the fashion process, Rose tells a rich story of 70s and 80s Jamaican communities through the aesthetics she has witnessed in her own community, like permacreased pants that she blows up in proportion. She is a magician gathering very personal remnants of culture from a satin hat—well, in this case, pants.

So Martine @ Balenciaga?

It’s true that Demna Gvasalia is also heavily inspired by Margiela. He and Rose are members of a large episteme of designers bearing the legacy of disruption, deconstruction, and subversion.

Despite what some may say about him, Demna’s work grasped the fabric of culture, creating satirical takes on war, fragmentation, the internet, and celebrity. At times, his creations were autobiographical, carrying the mark of strife and instability he witnessed in Georgia with intelligence and wit. But a critical difference between him and Rose, while they both interact with real cultural material, is the sentiment of their designs.

“Lately, his shows have seemed frozen in a mode of cynical, even nihilistic commitment to sweatpants and unappealing suits” says Rachel Tashjian in the Washington Post. There can be purpose to cynicism, but Demna’s final seasons at Balenciaga post-scandal felt increasingly lazy and out-of-step with the collective cultural consciousness. Many were skeptical about whether his provocations were moving the needle forward.

Perhaps in a world of backsliding civil rights, irony alone is not enough. Martine Rose gives us solutions—namely, solace in our cultural communities.

“It’s very easy to find a formula that works and trot that out for a little bit. That totally makes sense and that's what most people do. You find that magic thing and you keep doing it. Tam and I have never really done that.”

- Martine Rose (System Mag)

Rose’s propositions for dress continue to morph while she maintains a bold understatedness, fashioning radical acceptance through individuality and a refusal to stagnate. Her optimism is not blind; it guides us towards an understanding of the ways in which we move about the world and beside each other. She is provocative but not a mere provocateur, and her philosophy towards her own closet is telling of her purposeful design ethos. On the Cutting Room Floor podcast, she tells Recho Omondi that she doesn’t buy much, keeping selectively chosen pieces for a long time. At one point she describes denim as “a personal journal.”

Martine Rose’s designs take up space, but at the same time, they are humble theories about ourselves. Their restraint and mystery read like a poem.

Rose places fake noses on the models of her SS2025 and AW2025 collections, a vision of seductive nonconformity and a demonstration of clothes that ground us even as our faces change. These facial modifications are reminiscent of Margiela’s signature cloth coverings that obscured the full heads of models, presenting them as mirrors for every woman. Both designers withold visual elements to tease out the authentic.

“I’ve always said, it doesn't matter how big my brand gets, I always want to feel like a small brand. There's a certain looseness and a lightness that small brands have. It’s much harder to keep that sensitivity when you are boshing out thousands of one product or whatever, or you've got 50 people in your company. It’s a delicate balance.”

- Martine Rose (System Mag)

Rose could do a great job at Balenciaga, but I wonder more about whether taking the role would be a beneficial from her perspective. Why do we assume that people want to go to these big houses? Yes, she would be allocated financial resources, but also more restrictions, expectations, and levers to balance. Rose has been cultivating her work and consistent style for years, so to what extent would moving to a heritage house advance her design language? Would the codes of Cristobal inspire her?

Just based on design ethos, I think that she would have been a fabulous pick for Margiela, but what’s done is done. Still, who knows. Sabato was ousted from Gucci after just two years. Sorry Glenn, anything can happen!2

“It’s just this real interest in people, and in clothing, and in what clothing says about someone’s personality – where they’ve come from, where they’re going.”

- Martine Rose

I thought about Martine Rose a few times when I was at Berlin techno club Berghain last winter. The cold traveled up my nose, as my roommate and I cradled paper cups of hot coffee in the most silent door line I’ve ever experienced. I left for a moment, to slip around the corner and pee in a little alley —there were no bathrooms in sight. It felt funerary, a crowd in dark coats in quiet anticipation. There was, of course, the slight ego-lift of going somewhere Elon Musk was rejected. Sue me.

The former power plant-turned-venue rose from the ashes of the Ostgut club in 2004, its roots in queer nightlife. How much has it changed since then? Was this still a stronghold of expression or has the magic of the club begun to dissolve? I wondered about the comings and goings of subculture and remembered Rose’s shows about subversive 90s nightlife.

It was 11am on Sunday, probably the best time to get in. Many of the people in front of me looked like backpackers, from a slim German man in a grey leather jacket and beanie, to a short Asian woman with a buzzed head carrying a hiking bag. I wore my everyday combo that winter: the favorite gray coat, furry vest to block the wind, and grey wide-leg jeans.

Inside, the palatial brutalist architecture opened up to a crowd of people in gimp suits and sheer outfits. I wondered about techno-tourism and whether it had watered down the ethos of the club, whether I was part of that corrosive process as a foreigner. The day before, I watched as a gaggle of American fraternity brothers stood uncomfortably around the edges of the Kit Kat Club dance floor, tugging at matching latex shorts and plastic buckled armbands, perhaps a bulk purchase from the costume supply store. They made it past the bouncer but did not seem to be enjoying themselves.

There is so much chatter on TikTok about the politics of the club door, an extension of vociferous dialogue about how we choose to differentiate ourselves with personal taste, wielding it to gain access to spaces.

We need to stop being so calculated and let daily whims guide the invisible hand of style. It’s not that serious. I thought about how if I didn’t wear stuff I genuinely liked, I’d end up just like the frat guys at Kit Kat.

I spent seven sober hours in a glittering wave of music and limbs. It was the best sound system I have ever experienced. Every so often, my travel buddy and I ambled up to the bright smoking area for a break, a stairwell where pale white light streamed in. Right before I left, I saw the most magnificent tattoo of angel wings under a man’s gauzy top, an inky window.

Alongside memories of freedom through dance, I think of my favourite Martine Rose’s collection, FW2024:

“It was part Vogue ball, part riotous community fund-raising event—a night packed with laughter, warmth, and a wow-factor surprise”

- Sarah Mower (Vogue)

The first showing was just for London friends and family. No phones, exultant cheering, and a fuzzy spotlight hovering to club classics. Take a closer look. Notice the sleeve lining that extends past the wrist, mimicking a shirt cuff peeping out. A fresh color story. Interesting belts. Rose was inspired by outlandish countercultural club nights at Kinky Gerlinky in the 90s, frequented by Boy George and Leigh Bowery. Each model promenaded down the catwalk as if striding into a party, confident and debonair. The scene was captured by a VHS film, and she staged a surprise second showing for the fashion crowd during Paris menswear week.

It was all about gesture, with Rose’s signature wacky, elegant renditions of menswear classics. It was about joy and swagger, jackets and ponchos molded to the body like sculptures, carrying windswept motion.

In my dreams, I hear Rose’s swan songs to the magnificent and the offbeat, to celebrations of difference. In the night, I don a raucous suit and think of the moments when the soul feels most translucent. The times when you swirl around and find your friends dancing beside you, suspended in the smoky air. Music pulses through the lapels of your being until you lock eyes with someone you love. In that split second, everything fits just right.

Favourite independent fashion critic rn, go look at her stuff!

I agree that he is talented, but lowkey I think she would be more interesting at the house.